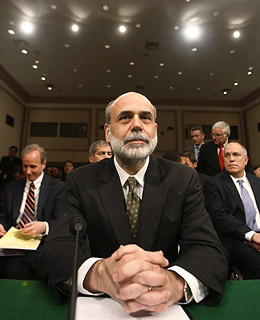

After the long, eventful reign of Alan Greenspan at the U.S. Federal Reserve, his successor Ben Bernanke promised a duller, more predictable tenure when he took charge in February 2006. Then history intervened, in the form of the subprime-mortgage crisis that erupted last year. Since then the soft-spoken former Princeton professor has been at the helm of an increasingly bold, increasingly unconventional, increasingly controversial effort to keep America's housing problems from toppling the global financial system.

Early in his career as an economist, the South Carolina-raised and Harvard-and MIT-educated Bernanke, 53, studied the causes of the Great Depression and concluded that the "malfunctioning of financial institutions" was a major culprit. Malfunctioning is what the market for mortgage securities started doing last summer, and since then many other credit markets have followed suit. The result has been what many have called the worst U.S. financial crisis since the Depression, and Bernanke has been going to unprecedented lengths to keep it from getting worse. His most dramatic intervention so far came in March, when the Fed forced and helped finance a shotgun marriage between about-to-fail investment bank Bear Stearns and JPMorgan Chase.

Bernanke's efforts have been a success — sort of. Loans are still being made (although not nearly as many as there were before last summer), and the world's ATMs are still spitting out cash. But the Fed's boldness has raised troubling questions about financial risk, moral hazard and the role of regulators that will occupy Wall Street and Washington for years to come. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy appears to have fallen into recession, the dollar is testing its all-time lows, and while credit-market jitters have receded, they certainly haven't gone away.

Dull predictability? Only in Bernanke's dreams.